Building a makerspace without walls

Long before anybody coined the word “makerspace,” Stanford’s Product Realization Lab was providing students with the facilities to build anything from robotic limbs to exotic musical instruments and interactive art.

But now, with the COVID-19 pandemic keeping most students off campus, the university has launched a pilot program to ship students a key piece of equipment for building and inventing at home.

Every student enrolled in one of 14 courses that require making prototypes, from classes in mechanical engineering to those in sculpture and music, will receive a 3D printer to use at home. Some 450 students will take part, and they can keep the printers after the course is over.

This would have been unthinkable a few years ago. But prices for professional-quality 3D printers have plunged so much that it’s now possible to consider. Each of the new printers, along with the materials to make products, will cost about $270 per student. That’s about the cost of some textbooks.

The hope is that the program could spur a new distributed and decentralized approach to design and invention, even after the pandemic has abated.

“We’ve come across a tipping point where it can actually be more efficient and economical to just give students this hardware,” says Steven Collins, an associate professor of mechanical engineering who helped map out the effort. “It’s a great opportunity to enhance students’ experiences during the pandemic, but it could also be valuable afterward as well.”

But success will depend on more than just shipping out free printers. It will require giving students considerable technical support, as well as students and faculty collaborating with each other in what amounts to an online makerspace.

“A 3D printer is cool, for sure, but it’s just a tool,” says Marlo Kohn, associate director of the Product Realization Lab. “You have to make sure students have the context for how and why to use that tool.”

Each printer is small enough to sit on a large desk, but students will have to assemble, maintain and learn how to use them. They will also have to troubleshoot problems and perhaps make repairs.

A small group of trained course assistants at the Product Realization Lab is preparing background material and will provide support through group tutorials and one-on-one sessions as needed. The support staff will have a supply of spare parts because some machines will inevitably break.

Beyond that, the group has established a dedicated Slack workspace and website where students from all the classes can share ideas and brainstorm about problems. With everyone working on their own, say Collins and Kohn, collaboration will be crucial. Students will be posting about their projects on a channel called “I Made a Thing.”

“We’re trying to create a place where students can share their struggles and solutions, and celebrate each other’s successes,” says Collins.

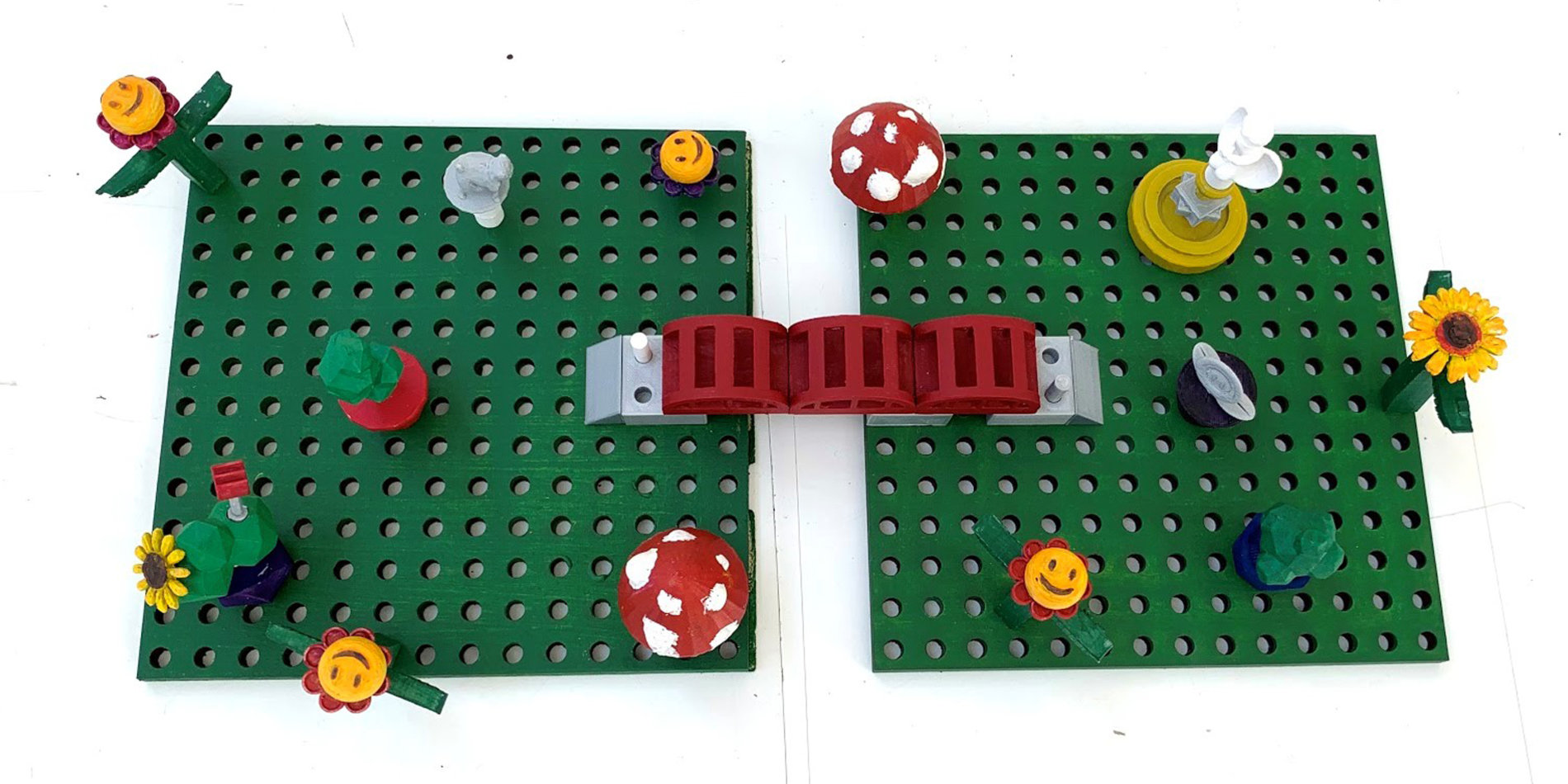

The PRL already has a rich history of spurring inventors and artists across disciplines. Students have built robots, with a big share of the parts made from the lab’s 3D printers. Music students have used the printers to make mouthpieces for exotic wind instruments and resonators for violins and cellos. In a sculpture class this fall, students will collaborate on projects that transform or replicate objects in the real world.

By decentralizing the access to a key piece of prototyping equipment, faculty members say, the program could greatly expand the range of people who become inventors and builders. “The analogy here is to personal computers,” says Collins. “Forty years ago, very few people used one. Today, everyone assumes that every student has one.”

Kohn says she had been nervous initially. Would the equipment be good enough? Would students be able to absorb the broader principles of design prototyping if they were working in isolation?

But Kohn says the inexpensive new printers are amazingly good, and she predicts that they will indeed open up new opportunities.

“We’ve had some students before with 3D printers in their dorm rooms, as the costs came down, but the quality was quite low,” Kohn says. “These printers have been getting much, much better. My family and I just assembled ours this weekend, and I’m truly shocked at the quality of the machine itself and of the prints.”

The project is being funded by the university, the School of Engineering, the Department of Mechanical Engineering and the university’s long-range vision committee on maker spaces.