Through a critical lens: Students identify unmet healthcare needs

For 10 weeks this summer, 12 undergraduate engineering students spent their free time shadowing physicians in the Stanford hospitals looking for problems in care that could potentially be addressed through technology innovation. They interviewed doctors and nurses to validate the issues they saw. They conducted research to understand stakeholder perspectives and the potential market opportunity around developing new solutions. And by the end of the Stanford Byers Center for Biodesign’s summer needs finding program, the students had completed an abbreviated version of “identify,” the first and most important phase of the biodesign innovation process.

The students were motivated to take the no-credit course by their interest in exploring the intersection of health care and engineering, the opportunity to “approach human health from a non-clinical perspective,” according to one student, and what another student described as “the chance to get exposure to the inner workings of the hospital and view the world of health care through a critical lens.”

Ultimately, the undergraduates uncovered needs that ranged from addressing process inefficiencies to improving clinical outcomes. Some highlights:

Diabetes care in teenagers

Abby McShane, a bioengineering sophomore, watched Stanford pediatric endocrinologist Dr. Priya Prahalad meet with a patient, a young man with type 1 diabetes in his first year in college. The patient regularly had a blood glucose level nearly twice the recommended maximum, and admitted that he frequently forgot to check his glucose around lunchtime. Asking questions and delving into secondary research, McShane learned that poor diabetes management was a recurring problem in young people transitioning to college. Not only can competing academic, economic and social priorities detract from a commitment to chronic disease management, but teenagers often don’t see the consequences of not being compliant. Adding to the problem, the transition from pediatric to adult care is awkward physicians tend to specialize in treating children or adults, with neither group well-equipped to manage the unique needs of young adults. The consequences of this gap in care are serious; men ages 20–29 with type 1 diabetes have a mortality rate three times higher than the general population. Within that group, 68% of diabetes-related deaths are due to acute complications of not closely controlling blood glucose.

Vascular access in obese patients

Jill Rogers and Saket Myneni, a sophomore and first-year student in bioengineering, respectively, were planning to observe a robotic surgery to remove a cancerous kidney from an obese patient. However, before the procedure even began, they watched surgical residents and nurses struggle for a full 90 minutes to place an arterial line into the patient. An arterial line is a thin, flexible catheter inserted into an artery in the arm or leg to closely monitor blood pressure in patients who have a high risk of rapid blood loss. The problem Rogers and Myneni observed was that layers of subcutaneous fat blocked access to the arteries, making it nearly impossible for the medical team to see or feel them. Even ultrasound guidance provided little help. Negative consequences included increased time under anesthesia for the patient, higher risk of complications and excess, expensive time in the operating room. Through research, Rogers and Myneni confirmed the magnitude of the problem; 1 in 3 Americans are considered obese by medical professionals, and there is an even higher prevalence in surgical patients due to associated health problems.

Disposable equipment waste

In the course of her observations, Annie Brantigan, a junior in electrical engineering, was surprised by the amount of disposable medical equipment wasted during surgical procedures. The problem is that sterile supplies such as surgifoam, clips and sutures are opened in preparation for a procedure but often not used. Because these materials are no longer sterile, they then must be thrown away. Through research, Brantigan learned that roughly 13% of the cost of a surgical procedure comes from wasted disposable equipment, and that total, averaging around $1,000 per procedure, is often billed to the patient. The cost of the wasted equipment increases further as hospitals must pay by the pound to dispose of biohazard waste.

Presenting the needs

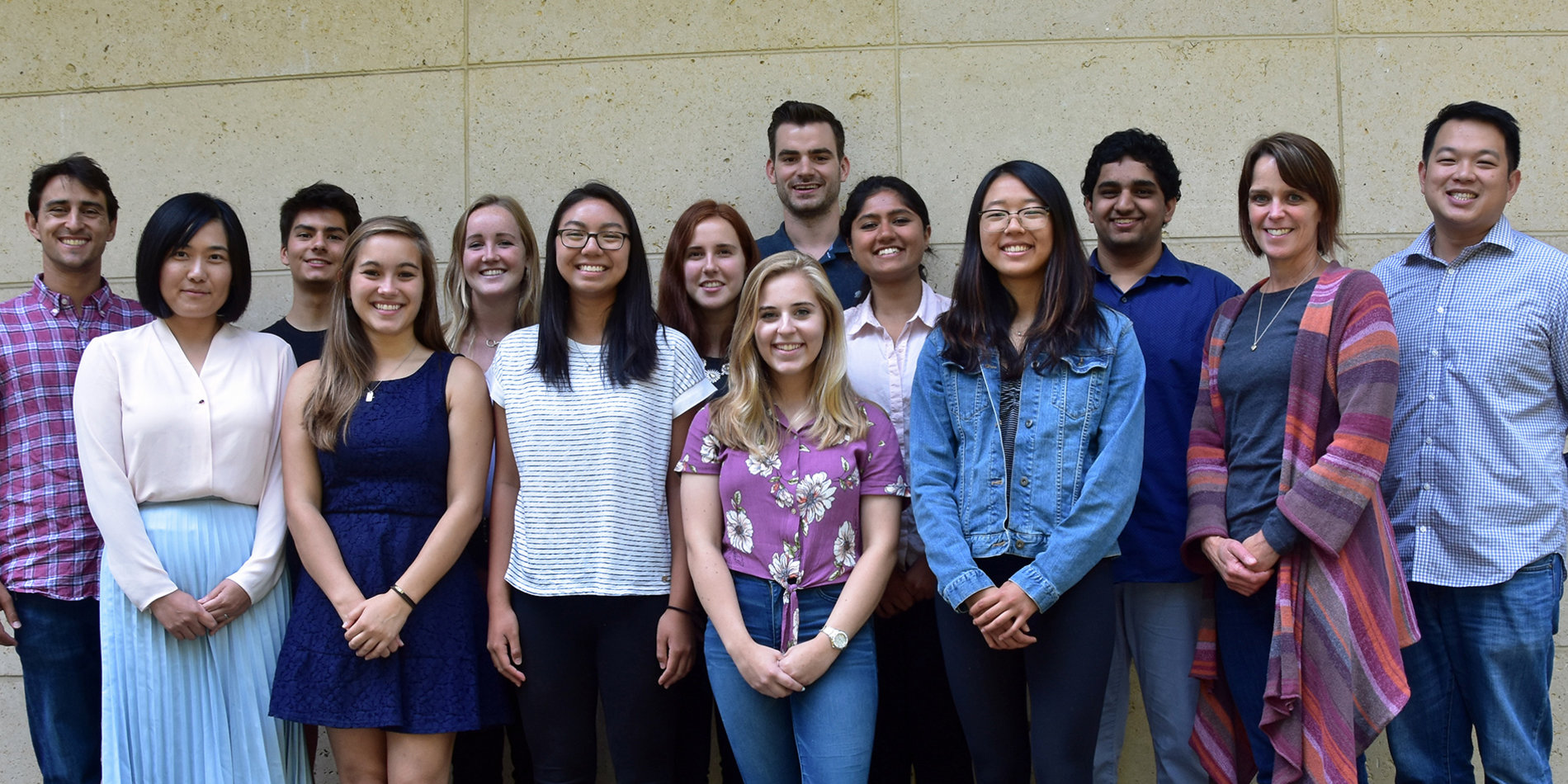

At the end of the quarter, the students presented the final needs to the Stanford Biodesign teaching team: Lyn Denend, Richard Fan, Justin Huelman, Ross Venook, Alexei Wagner, MD, James Wall, MD, and Marta Zanchi. They were then given the choice to continue working on their needs or “donate” them for other students to work on in Biodesign’s project-based courses. According to Brantigan, who decided to share her need with others, “It was motivating to know that I had uncovered an important problem, and that other students would have the chance to think about how to potentially solve it during the coming academic year.”

Other positive feedback from the students revolved around what they learned about themselves and their career aspirations as a result of the experience. One student observed “how many opportunities there are for improvement in medicine”; another found a “new appreciation for the power of engineering”; and a third reported, “It helped me understand that there are opportunities to be meaningfully involved in health care without having to be a doctor first.”